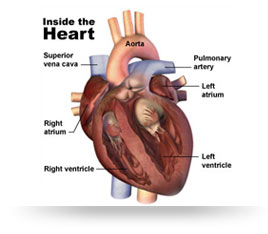

The heart has four chambers: The two lower pumping chambers of the heart are called the ventricles, and the two upper filling chambers are the atria. In normal circulation, blood that returns from the body to the right-side filling chamber (right atrium) is low in oxygen. This blood passes to the right-side pumping chamber (right ventricle), and then travels to the lungs to receive oxygen. The oxygen-enriched blood returns to the left-side filling chamber (left atrium), then moves to the left-sided pumping chamber (left ventricle).

The blood is then pumped out to the body through the aorta, a large blood vessel that carries blood to the smaller blood vessels in the body to deliver oxygen. The right and left-sided pumping chambers (ventricles) are separated by shared wall, called the ventricular septum.

In a person with a ventricular septal defect (VSD), there is an opening in the wall (septum) between the right ventricle and the left ventricle. You might hear this type of problem also referred to as a "hole in the heart." As a result, when the heart beats, some of the blood in the left ventricle (which has received oxygen from the lungs already) is able to flow through the hole in the septum into the right ventricle. In the right ventricle, this oxygen-rich blood mixes with the oxygen-poor blood and is directed via the pulmonary artery back to the lungs. The blood flowing through the hole creates an extra noise during the listening exam of the heart, known as a heart murmur. The character of the heart murmur, along with other specific heart sounds that can be detected a cardiologist, may be clues that a person has a VSD.

There are different types of VSDs, based on the exact location within the ventricular septum. In addition, they can vary in size. The symptoms and medical treatment of the VSD will depend on these features. Sometimes, VSDs can also be present as part of more complex types of congenital heart disease.

Signs and Symptoms

VSDs are usually found in the first few months of life by a doctor during a routine checkup. The size of the hole and its location in the heart will determine whether someone experiences symptoms of VSD. Most teens with VSD probably don't remember having it because it either goes away on its own or is diagnosed so early in childhood that there's no memory of any surgery or recovery.

Teens who have small VSDs that haven't closed yet usually experience no noticeable physical signs other than the heart murmur that the doctors hear. They may need to see a doctor regularly to check on the heart defect and make sure there aren't any problems.

The very small number of teens with moderate and large VSDs that haven't been treated in childhood may notice some symptoms, however. These include shortness of breath, a feeling of tiredness or weakness (especially during exercise), poor appetite, and trouble gaining weight. Fortunately, though, advancements in medicine during the past few decades mean that most kids with moderate to large VSDs are treated long before the VSD ever causes physical symptoms.